Newcastle University

A top tier international university excelling in research, teaching and partnership working

Founded: 1963

Organization Details

Full Name: The University of Newcastle upon Tyne

Field: Higher Education

Founded: 1963

Headquarters: Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU

History and Activities

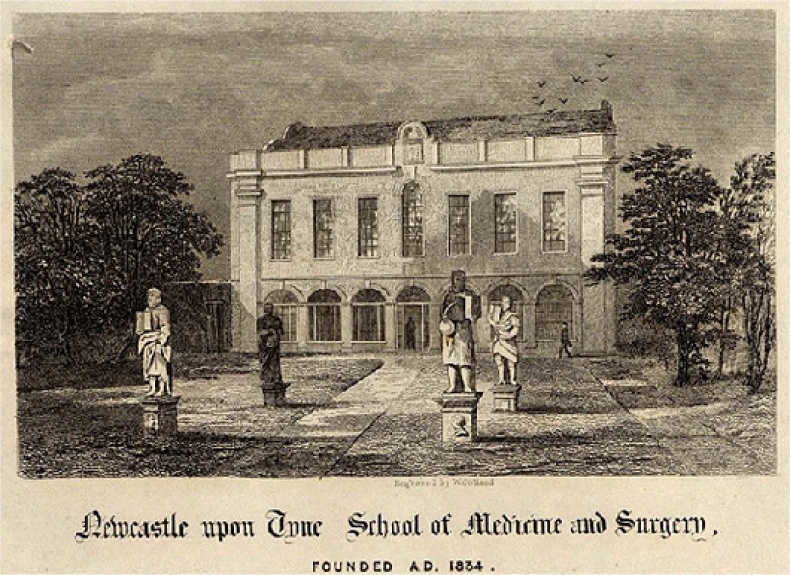

In the early 19th century, Newcastle was a rapidly expanding industrial town with a growing demand for medical services, inspiring six medical practitioners, including Sir John Fife, to begin in 1832 delivering courses on anatomy, chemistry and medicine in rooms at Bells Court on Pilgrim Street. This initiative led to the formal establishment of a medical school in Newcastle on the 1st October 1834 at the Barbour Surgeons Company Hall in the Manors. Funding came from public subscriptions, the largest of which were £100 from the Newcastle Corporation, £50 from the Duke of Northumberland, and £25 each from John Fife and Matthew White Ridley.

The school recruited well and in 1852 became part of the University of Durham under the long-winded title The Newcastle upon Tyne College of Medicine in connection with the University of Durham. Thus began the long-standing connection between Durham and Newcastle in higher education that lasted for 111 years down to 1963. When serious discussions began amongst the business and professional elite of Newcastle in the 186Os about the formation of an applied scientific institute of higher education to serve the many booming industries of the North East, Durham University, willingly became involved in order to broaden its academic base beyond theology and the classics. Dean William Lake, warden of Durham University between 1869 and 1894, stepped forward with an offer of support of £1,000 a year for six years on condition that an equivalent sum was raised by public subscription. An appeal for £20,000 was immediately launched “to provide advanced scientific education in four northern counties and the north region and especially to teach science in applied (...) mining, agriculture and manufacture”. The initial list of subscribers committed to funding the college for six years. The industrial leaders of the North East stepped up the plate, including William Armstrong (£100 a year), Joseph Pease MP (£50 a year), Isaac Lothian Bell (£50 a year), amongst others. The initial amount raised was in excess of £3000, enough to fund the college for at least three years of the proposed six-year developmental phase. Lectures began at the Newcastle College of Physical Science on the 1st of October 1871. The first students were attracted to the college by the prospect of becoming mining engineers, beginning the strong identification of Newcastle University with engineering excellence, which continues today.

In 1886, work began on what we know today as the main campus of Newcastle University, the first suitably red-brick building progressing in stages on land then known as Lax’s Gardens, completed in 1904. Yet, despite the support of numerous benefactors, a large mortgage was required to complete what then became known as Armstrong College. The German-born electrical engineer, Theodore Merz, deserves lasting credit for personally underwriting the mortgage needed to complete the new building. Indeed, it was Merz, solicitor Robert Spence Watson and the chemical engineer Robert Robey Redmayne who provided much of the leadership necessary to get the new university college off the ground. The building was formally opened by King Edward VII on the 11th of July 1906. Its existence, which depended on the philanthropic contributions of the many, not the few, offers proof positive of the power of subscription philanthropy during the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Newcastle, unlike other provincial institutions of similar vintage, lacked the support of a wealthy local family such as the Boots in Nottingham or the Wills in Bristol.

As the 20th century progressed, the University grew larger, offering more courses to more students. Much of this growth would not have been possible without significant gifts from generous benefactors. The gifts are too numerous to list, but by way of illustration:

- Sir Arthur Sutherland gave £12,000 to construct a dental school in 1931 and £200,000 in 1936 to construct a new home for the medical school.

- Sir Cecil Cochrane gave 20 acres of land, which became known as Cochrane Park in Heaton. It is Newcastle University’s principal competitive venue for football, rugby and cricket. He also donated monies to build the Students’ Union in 1925, a gift given anonymously at the time.

- In 1911, Dr John Bell Simpson gave £10,000 to construct the King Edward VII building for the School of Art.

- Emily Matilda Watson, who died in 1913, bequeathed £10,000 to the College of Medicine and £5,000 to Armstrong College. The gifts were used to pay off part of the mortgage on the Armstrong building and to build university accommodation for 40 female students. Opened in 1915, the Easton Flats continue to house postgraduate students.

The growth of higher education in Newcastle under the wing of the University of Durham was highly beneficial for both parties. The College of Medicine and Armstrong College prospered, growing more rapidly than the Durham colleges, and leading in 1909 to the formal creation of two divisions of the University, Durham and Newcastle. The Dean and Chapter of Durham Cathedral was then replaced as the governing body of the university. The Newcastle division was re-modelled as King’s College of the University of Durham in 1937 following the recommendations of a Royal Commission. In 1963, King’s College formally seceded to become the University of Newcastle upon Tyne.

In the first half of the 20th century, philanthropy served mainly to support the provision of buildings and other educational facilities, but since that time support for major research initiatives has moved centre stage. The medical school has attracted a great deal of philanthropic funding, particularly for cancer research. For example, the Sir Bobby Robson Cancer Trials Research Centre has been supported by a substantial donation from the Sir Bobby Robson Foundation. The centre is housed at the Northern Institute for Cancer Research, established in 2001. In 2005, Sir Bobby opened a £10 million state-of-the-art building in honour of Paul O’Gorman, who tragically died of cancer aged just 14 years, jointly funded by Children with Cancer UK, Cancer Research UK, and the Higher Education Funding Council for England strategic initiative fund.

One of the best known contemporary university benefactors is the novelist Catherine Cookson. Her philanthropy was discreet and tended to champion causes with which she had a personal affinity. She suffered from telangiectasia, a blood disorder similar to haemophilia. In 1985, she donated £800,000 to establish a lectureship in haematology, to pursue research aimed at better understanding and eventually finding a cure for the disease.

As a result of the generosity of past and present generations of donors, Newcastle has built up a substantial endowment, partly controlled directly by the University and partly by a development trust. The endowment gives the University greater freedom than it would otherwise have to pursue bold new strategic initiatives. The first part sits within the main university accounts and was valued at £63.4 million on the 31st July 2017. The second sits within the University’s Development Trust, a registered charity, and was valued at £57.4 million at the 1st of March 2017, amounting in all to £120.8 million pounds. The income in the last financial year from endowment, donations and legacies was £9.0 million. Further to this, the university received £26.2 million in research grants from charitable trusts and foundations, giving a total philanthropic income of £32.5 million.

Vital Statistics (year to 31/07/2017)

| Total Income (TI):

| £487,900,000

|

| Philanthropic Income (PI):

| £35,200,000

|

| PI as % of TI:

| 7.2%

|

| Employees:

| 6,141

|

| Students:

| 26,409

|

| Endowment at Year End:

| £120,800,000

|

Website

https://www.ncl.ac.uk/

References

Bettsenson, E. (1971). The University of Newcastle upon Tyne, A historical introduction 1834 – 1971, Newcastle upon Tyne: The University of Newcastle upon Tyne.

Charities Commission. (2017). The University of Newcastle upon Tyne Development Trust and Other Related Charities, Available here (Accessed 17/10/2018).

Mining Institute. (2018). Past Presidents of the Institute, William Cochrane, Available here (Accessed 26/09/2018).

Newcastle University, Special Collections - Robinson (Marjorie and Philip) Collection.

Newcastle University. (2018). World-renowned architect donates archive and £1m to University, Available here (Accessed: 16/10/2018).

Newcastle University. (2017). Newcastle University - Integrated Annual Report, Available here (Accessed: 18/10/2018).

Nicholson, D. E. T. (1997). Obituary: Ernest Bettenson, The Independent, Friday 20th June, Available here (Accessed: 25/09/2018).

McCord, N. (2006). Newcastle University - Past, Present and Future, Newcastle: Newcastle University.

The Herald. (1998). Tributes and tears after the death of Cookson, 91, 12th June, Available here (Accessed: 26/09/2018).

Whiting, C.E. (1932). The University of Durham 1832-1932, London: The Sheldon Press.