Sharp, Dr John

1722-1792

Archdeacon of Northumberland

John Sharp was born in Rothbury, the son of Thomas Sharp (1693-1758), Archdeacon of Northumberland. The Sharps were a wealthy and prominent clerical family and John’s grandfather, also named John (1645-1714), had been Archbishop of York. The family’s wealth was built upon agriculture and cloth manufacturing in Yorkshire. Sharp attended Cambridge University, where he was awarded a doctorate in 1759.

When his father, Thomas, died in 1758, John inherited both the Archdeaconship of Northumberland and his seat on the board of trustees of Lord Crewe’s Charity.

It wasn’t until the death of his brother, Thomas (d.1772) who was head of the family at Bamburgh that John’s life work truly began. John’s first act was the full restoration of Bamburgh castle as a headquarters for the Lord Crewe’s Charity. He built a residence in the village for the trustees and a school for the children of Bamburgh’s poor families. He also rebuilt the ramparts and walls of the castle to provide a platform for a fog cannon and accommodation for up to 30 shipwrecked sailors.

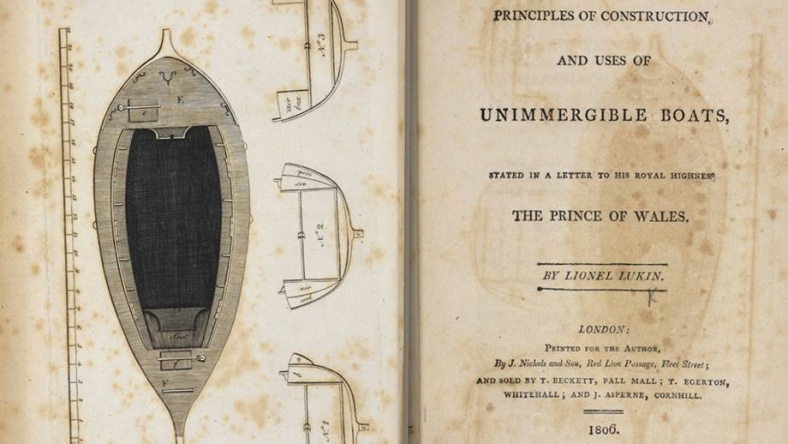

Sharp later combined his own personal wealth along with funds from the Crewe charity to fund an 8-mile patrol along the Bamburgh coast for survivors of shipwrecks. He commissioned Lionel Lukin in 1789 to construct an 'unimmergible' boat, an unsinkable boat, which was stationed at Bamburgh. The Lukin Boat was the first patented lifeboat in the world, and Bamburgh the first lifeboat station.

In the village of Bamburgh itself, Sharp took several initiatives that came to be known as the Bamburgh Charities. These included the Corn Charity (1766) that provided subsidised food to the poor. The Cheap Shop (1796) provided subsidised household goods and The ‘Surgery’ (1772-1920) provided free healthcare. Finally, Bamburgh Castle School provided education to both boys and girls from the village and later became a boarding school for orphaned and impoverished girls. A larger school was established in Bamburgh in 1877 for 120 children.

Sharp had many more ideas that either weren’t realised or didn’t work as intended, including the free use of agricultural machinery for local farmers. It is evident from his own personal contributions to the Crewe Charity and his enthusiasm for innovative ideas that John was a passionate social reformer. He had a singular interpretation of the vision of the charity’s founder, Nathanial Crewe.

On his death in 1792, Sharp gifted his personal library to Lord Crewe’s Charity which has been continuously maintained, first at Bamburgh and then since 1958 by Durham University North East Religious Learning Resources Centre. Sharp transformed not only the castle of Bamburgh but also the quality of life for the village and surrounding areas. The charities he established there survived long after his death. John’s greatest legacy is perhaps his influence on the direction of Lord Crewe’s Charity trust. His interpretation of Nathaniel Crewe’s will was a mandate for future trustees to support a wide range of charitable activities throughout Northumberland and Durham.

References

Blanchland Community Development Organisation. (2018). Blanchland History. Available here (Accessed: 06/08/2018).

Blackburn, C (2018). Blanchland history. Available here (Accessed: 06/08/2018).

Charity Commission: Crew Trust. (2018). Available here (Accessed: 06/08/2018).

Deoninck-Brossard, F. (2004). Sharp, John, Available here (Accessed: 30/05/2018).

Johnson, M. (2004). Crew [Crewe], Nathaniel, third Baron Crew, Available here (Accessed: 30/05/2018).

Lincoln College. (2018). Lincoln College History. Available here (Accessed: 06/08/2018).

Lomas, R. (2009). An encyclopaedia of North-East England, Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd, pp. 119-20.

Lord Crewe’s Charity. (2018). Available here (Accessed: 06/08/2018).

National Archive. (2018). Lord Crewe Entry. Available here (Accessed: 06/08/2018).

Stranks, C.J. (1976). The charities of Nathaniel, Lord Crewe and Dr John Sharp 1721-1976, Chester le Street: City Printing.

Whiting, C.E. (1940). Nathaniel Lord Crewe Bishop of Durham, 1674-1721, and his Diocese. London: The Sheldon Press.